'Settled,' perhaps, but still unsettling

50 years after it erupted in war, the Cyprus I knew is not likely to return

Years ago, I was having lunch in Houston with former State Department employee, and I mentioned that I’d lived in Cyprus when I was a child. He said he’d been stationed in Cyprus for a while in 1990s.

In 1974, Cyprus erupted in a war that divided the island nation’s citizens by their Greek and Turkish ancestry. Since then, a “green line” has split the island in two— The Greek Cypriot Republic of Cyprus, in the south, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, recognized only by Turkey.

I’ve spent most of my life hoping for a reconciliation that would reunite the two sides, to restore the country that I once knew.

At the time of my lunch meeting, the UN was trying, yet again, to broker a peace accord. I told my lunch companion that despite past disappointments, I hoped for progress. I would like to see the Cyprus situation settled.

He looked at me for a moment and said: “As far as the rest of the world is concerned, the Cyprus situation is settled.”

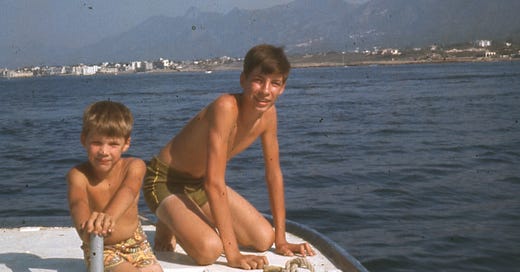

I knew he was right, but I didn’t want to admit it then, and I don’t want to admit it now. We lived in Cyprus in 1972 and 1973, before the war. I remember my family’s time there as a magical adventure. But as an adult, I also recognize that I was blind to the conflict roiling beneath the surface of the seemingly docile Mediterranean isle.

The 50-year anniversary of the coup attempt that led the the island’s division passed last week. Few news organization bothered to note the milestone. The capital city of Nicosia remains the only divided capital in Europe.

But life in Cyprus has moved on, and even during my last visit there, in 2009, I was surprised at how the division had become a part of the local life—if not accepted, at least tolerated by most residents. Compared with other ethnic conflicts in the region, such those between Israelis and Palestinians, the Cyprus situation has been placid for decades.

The Economist, one of the few news organizations to acknowledge the 50th anniversary, noted that with the admissions to the European Union of the Republic of Cyprus, and relative ease of moving between it and the Turkish-Cypriot north, the division has become manageable.

Freedom of movement and access to Europe have reduced the pressure on both sides to unify. For many Greek-Cypriots, unification has only a downside. They would have to share power with Turkish-Cypriots (and, indirectly, with Turkey itself). The difference in incomes (GDP per head is twice or more as high as on the Greek side than on the Turkish one) could cause economic upheaval.

In all, many Greek-Cypriots would see reunification as a “real risk of becoming Lebanon, and our parents already lived through that,” says Michael Sirivianos, an engineering dean at Cyprus University of Technology in the southern coastal city of Limassol.

[…]

“It saddens me to say, but I think the status quo has been very sustainable in Cyprus,” says Ahmet Sözen, a political scientist at Eastern Mediterranean University in the northern city of Famagusta. “The longer the division continues, the more concrete it gets.”

It saddens me to hear it, but I know he’s right. And while I would love to see the return of the Cyprus I remember, it’s possible that Cyprus never existed anyway. I was too young to grasp what was happening around us, and too in awe of the Crusader castles, daily snorkeling adventures, and captivating culture that surrounded us to notice anyway. Nothing can take away the magic of my memories. That Cyprus will always exist in perhaps the only place it ever did—my mind.

And as unsettling as I may find it, my friend was right. The situation is, for the most part, settled. Fifty years on, I’m glad that if the Cyprus has not found unity, at least it seems to have found peace.